This article was originally written 8th April 2020,

by Srikanth Narayanan.

Conventionally, therapeutic relationships are conceived as dyads with a therapist and a client. However, on the recent Wild Therapy training as part of some research I had initiated, we began to explore the edges of this convention and experiment with therapeutic triads. This was partly for convenience since we were a group of nine. But what emerged set many of us wondering whether triads could be a useful way of working with clients and others and started to clarify something about Wild Therapy as an approach.

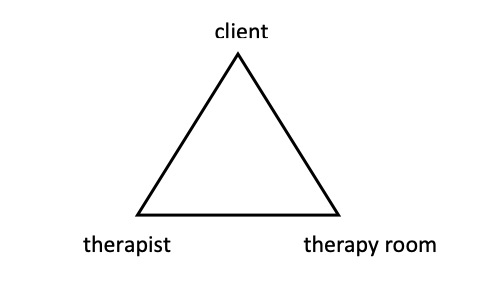

In some ways, there is always a relational third available if we widen our attentional field. A therapist working indoors with a client might see a triad in:

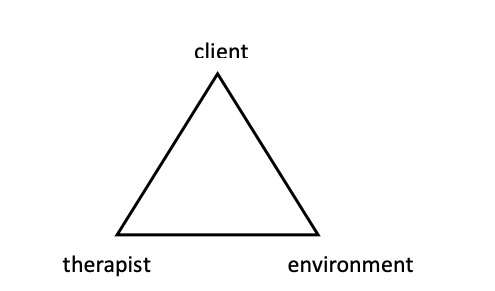

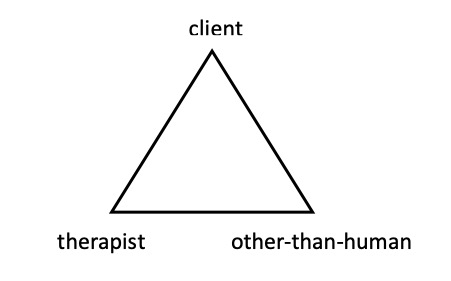

An ecotherapist working outside might see:

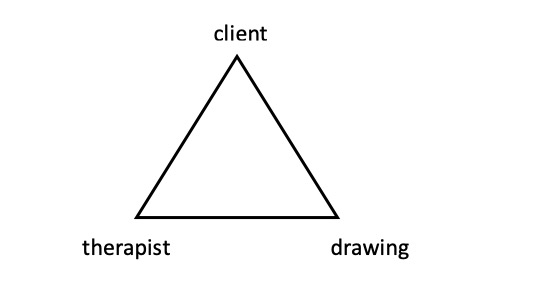

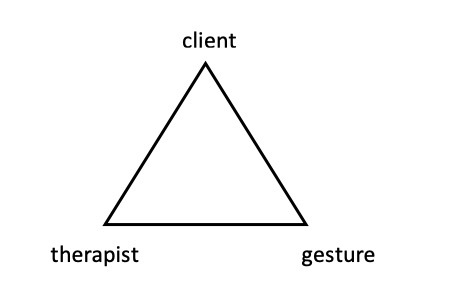

An art therapist working with a client with paper and pastels might see:

A movement therapist might see:

There are clearly many variations of this framing for therapeutic relationships.

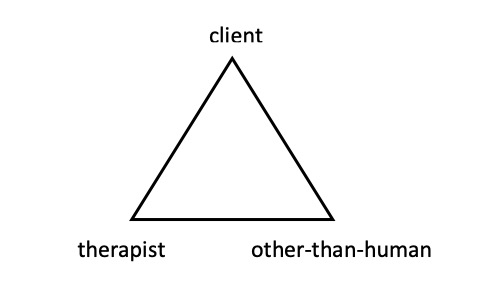

In Wild Therapy we might be particularly interested in:

For our experiments we wondered how it might be if the third was another human. One of the advantages of this is that if the third is a person, they can reflect directly on the experience of being in that position.

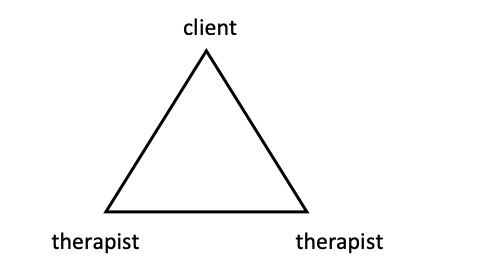

Some of our experiments involved two therapists and a client:

Within this framing, the other-than-human is still present in two ways. When we speak of the other-than-human, we may be referring to a specific instance of an other-than-human presence – a distinct but not separate thing – this leaf, this stream, this bag. Sometimes, however, we may speak of the other-than-human as a collective – the other-than-human. Perhaps this is similar to the way we use the same word ‘you’ in different ways: you (singular) and you (plural). In our human-focused triad, the other than human is present in both of these ways. Firstly, the other-than-human (collective) is the ground for the triad or the white page in the picture, and it always is. This doesn’t preclude a direct, intentional, explicit relationship with them. Secondly, the other-than-human (singular) might enter any of these triads (as might another human) in a specific instance. But the focus of this research was on how three humans might occupy these positions.

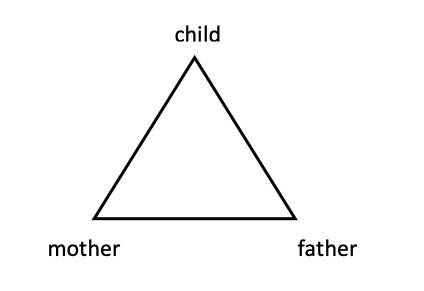

It felt as if there was a lot of flexibility in this setup for the therapist to hold different parts of the client and of the therapeutic process, and to do so more deeply than in a dyad. In one session it felt as if one therapist was, for a while, the driver, while one was the navigator. The two therapists could occupy different positions in relation to the client’s material and different styles of contact with the client, consistently and deeply through the session. Noticing also how much parental counter-transference was present in this frame it seemed that we were often echoing:

And it seems obvious that there would be therapeutic value in having these roles available to be embodied in a therapeutic relationship.

We also noted that it did not seem to matter too much whether the therapists were working with different approaches, although this was a concern when some of our triads were forming. As ever, with the therapists working to develop the relationships, the exact ways in which the therapists intervened mattered somewhat less than we imagined and perhaps offered the kind of integrated practice that as individuals we might struggle to provide. In some sessions, we also offered clients the chance to decide what they wanted the third person to be, with, for example, an additional therapist, an observer, a gatekeeper or lookout all being chosen.

Despite the excitement about the possibilities this offered, we also noted that working with clients in this way would pose a few obvious practical challenges. Would any client pay for two therapists? Who would select the therapists? What if the therapists didn’t know each other? Without doubt there would be much to consider about taking this into client work.

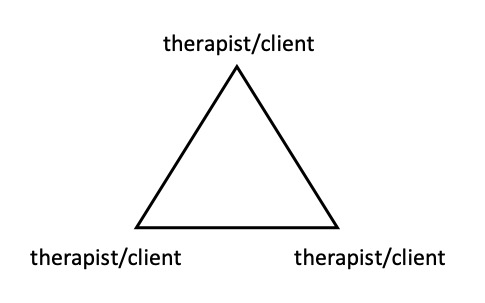

We also began to experiment with triads in which the traditional therapeutic roles were floating, rotating or undefined within a session. Anybody could implicitly identify themselves as a therapist or a client at any time, if those labels were helpful and without necessarily naming it for the others:

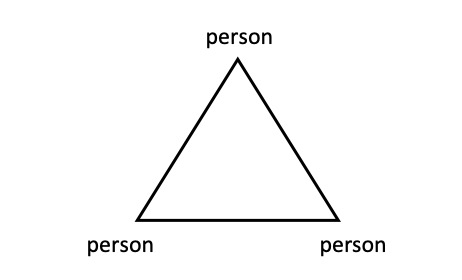

This might also, more accurately, be imagined as:

This was clearly bigger than a dyad but not quite a group. The complexity of this therapeutic situation — and with three people it was hard to slip back into roles unlike in a dyad where it is easier to take it in turns and one person’s role can be defined by the other’s choice — meant that the therapy soon became less obviously about any one person’s material or even the interpersonal material that was present yet practically impossible to track, and more about the task of being in relationship with each other and co-creating therapy. It was as if the personal became immaterial; the notes we were each playing less audible and less important than the music we were making together, filled out by the orchestra of all that was around us. This experience started to feel like a wild edge of therapy. Indeed one of the most exciting reflections about this was that if we can form therapeutic relationships like these in which it is not clear who the client is, it would spell the end of therapy as a paid profession.

But before we arrive at the end, I want to suggest that this is a wild edge that is always available to us, no matter how we are working or, indeed, how many of us are working. If there is always a third available to us, we always have the freedom to shake off our roles and trust that we will be held, with our clients, by the third in our therapeutic situation. I find myself asking how might it be for me to be that vulnerable and that congruent in a client session? And what stops me from allowing that?

Coming back to being a Wild Therapist, all of this leads me to wonder how much more I can trust the other-than-human in our relationships with a client, letting go of my role as a therapist and more fully surrendering to the other-than-human aspects of myself.

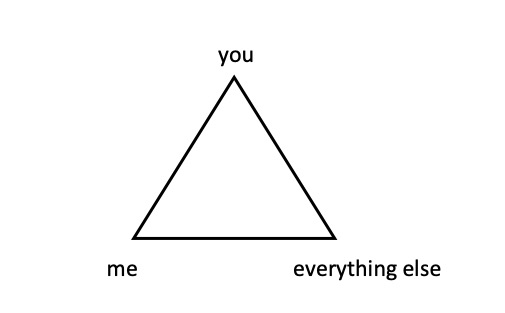

And as I do that, I find myself consciously invoking the following frame more and more in my work:

Here is a wild edge that only requires a perceptual shift, albeit a courageous one, trusting in all that is much more than us. Perhaps that says something about the approach of Wild Therapy.